April 2021 Horticulture News – Gardening, Bees, and Pests

go.ncsu.edu/readext?787227

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Starting Vegetable Seeds

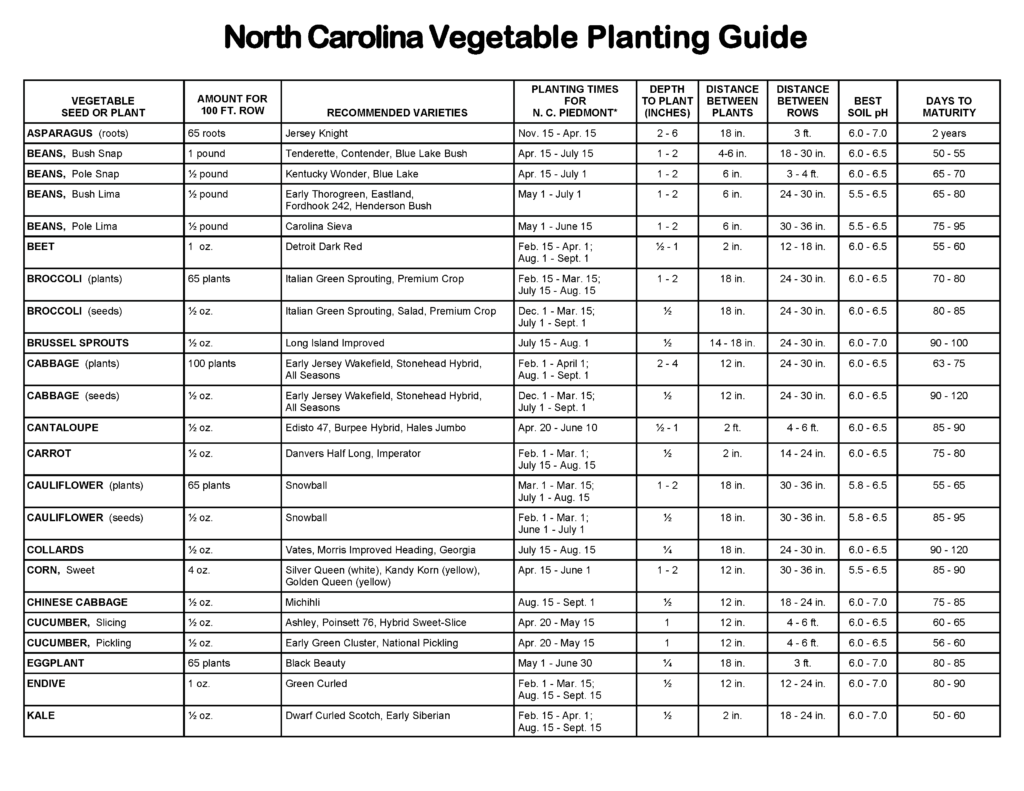

Growing your own transplants from seeds indoors can give you a head start on your vegetable garden. Seedlings are often started indoors four to 12 weeks before the last spring frost. A common mistake is to sow the seeds too early and then attempt to hold the seedlings under poor environmental conditions (light and temperature). This usually results in tall, weak, spindly plants that do not perform well in the garden. To obtain vigorous plants, start with high-quality seed from a reliable source.

A display rack of vintage seed packets.

Select cultivars which provide the plant size, fruit, and growth habit you want. Choose cultivars adapted to your area. Purchase only enough seed for one year’s use, since germination decreases with age. The seed packet label usually indicates essential information about the cultivar, the year in which the seeds were packaged, the germination percentage, and whether the seeds have received any chemical treatment.

A wide range of media can be used to germinate seeds. With experience, you will learn to determine what works best for you. The germinating medium should be rather fine in texture and of uniform consistency, yet well aerated and loose. It should be free of insects, disease organisms, nematodes, weeds, and weed seeds. It should also be of low fertility and capable of holding moisture, but yet be well-drained.

Purchase commercial potting media containing fine pine bark, peat moss, and perlite. Do not use garden soil to start seedlings; it is not sterile, it is too heavy, and it does not drain well. Plastic cell packs can be purchased to sow your seeds in. When using cell packs, each cell holds a single plant. This method reduces the risk of root injury when transplanting. Peat pellets, peat pots, or expanded foam cubes can also be used for producing seedlings. Be sure to keep the media evenly moist and don’t let it dry out.

For more information on vegetable seeds and other topics please contact the N.C. Cooperative Extension, Franklin County Center at 919-496-3344 or Colby Griffin at colby_griffin@ncsu.edu.

Ambrosia Beetles

If you have woody ornamentals and trees in your landscape you may have noticed damage from the granulate ambrosia beetle. This pest was introduced from Asia in the early 1970s. It has since spread throughout the Southeast. An infestation can be identified by toothpick-like strands protruding up to 1.5 inches from trunk of the host plant. These strands of boring dust are produced by the female beetle as she begins to excavate her gallery. The strands are fragile and are easily broken off by wind or rain leaving only pencil-lead-sized holes.

Ambrosia beetle damage to maple tree By Laura Lazarus, North Carolina Division of Forest Resources, Bugwood.

Individual plants may contain from one to hundreds of individual beetles. Ambrosia beetles become active around the first of March in the North Carolina Piedmont and usually peak by early April. Timing is dependent on local weather conditions and beetles can attack trees much earlier during warm spells. Ambrosia beetles remain active through the Summer and into the Fall. Trees located in nurseries are attacked primarily during the Spring but trees within the landscape may be attacked all summer.

Females bore into twigs, branches, or small trunks of susceptible hosts. They excavate tunnels in the wood, introduce ambrosia fungus, and lay eggs to produce a brood. It is the growing fungus on which the beetle grubs feed, not the wood. The beetles enter trees in early Spring and emerge as adults 55 days later. Ambrosia beetles primarily attack thin-barked, deciduous trees. The most common trees attacked in North Carolina are dogwood, redbud, maple, crape myrtle, and Japanese maple. Landscape trees may survive attacks but should be monitored for dieback and removed if necessary.

Homeowners have few products available that contain the active ingredients permethrin or bifenthrin that may be sprayed on the trunk. However, these only work as prevention and will not work once the beetle is inside the tree. Whenever you decide to use pesticides be sure to also follow the label and recommended dose. It is best to maintain healthy plants to reduce and outgrow any damage from Ambrosia beetles.

For more information on insect pests and other topics please contact the N.C. Cooperative Extension, Franklin County Center at 919-496-3344 or Colby Griffin at colby_griffin@ncsu.edu.

Maple Eyespot Gall

Maple Eyespot Gall on a maple leaf by Matthew Bertone, North Carolina State University, Bugwood.

Maple eyespot galls are brightly colored red and yellow spots that appear on the surface of red maple leaves. These colorful spots are caused by the ocellate gall midge. Although rarely seen, adult ocellate gall midges are small mosquito-like flies. Maple eyespot gall midges occur throughout the range of red maples, which includes all of the Eastern United States and parts of the Central United States.

This fly deposits eggs exclusively on the underside of red maple leaves. This causes a chemical response in the leaf resulting in gall formation. This gall is rarely abundant enough to cause injury to the tree but some people find them to be an aesthetic problem. Gall midges emerge from the soil as an adult in early May and lay eggs in the underside of leaves. The larvae develop within the leaf gall. As a result of hormones, the midge injects into the leaf, it develops bright red and yellow rings around the site of larval development. There is a darkened, more elevated point in the center of the ring where the larva resides on the leaf. In 8 to 10 days, the larva will drop from the leaf to the ground where it will pupate in the soil. There is only one generation per year so these pupae will remain in the soil until they emerge as adults the following May.

Monitoring includes surveying the tree canopy for leaves exhibiting red and yellow rings on the leaf surface. These galls appear very similar to leaf spot symptoms caused by plant fungal diseases. Hold a suspected leaf gall up to a light source to look for a darkened larval silhouette in the center of the ring. Control is rarely warranted. These galls rarely become abundant enough to cause damage.

For more information on pests and other topics please contact the N.C. Cooperative Extension, Franklin County Center at 919-496-3344 or Colby Griffin at colby_griffin@ncsu.edu.

Bee Habitat

If you build it they will come. This is usually the case when planting pollinator-friendly plants. By providing the necessary resources pollinators such as bees may thrive. However, hazards may prevent them from thriving.

Bee feeding on a flower.

Research indicates this situation exists for bees located within urban areas. Urban yards can be tough for bees and pollinators. There are often not enough flowers, or the wrong kind of flowers, so people compensate with pollinator gardens. However, cities are also hot, due to impervious surfaces and the urban heat island effect.

Wild bees differ in how well they tolerate high temperatures. Research states that regardless of the amount and diversity of flowering plants, bee populations declined at extremely hot locations. The most affected were small bee species such as sweat bees. Total populations declined 41% for each degree Celsius of warming. Wild bee abundance also declined in areas with more impervious surfaces like roads and sidewalks – which is also bad for honeybees.

If you live within an urban area there isn’t much you can do about the impervious surfaces surrounding you. However, if you plant a diversity of and an abundance of flowering plants you can reduce the negative effects of the urban environment. You can also cool the hardened surfaces within your home landscape by planting trees to shade those surfaces to help cool them down.

For more information on bees and other topics please contact the N.C. Cooperative Extension, Franklin County Center at 919-496-3344 or Colby Griffin at colby_griffin@ncsu.edu.

Felt Scale

As warmer weather settles in so does the inevitable increase in pests and pathogens in the landscape. One of these pests that can affect our trees and shrubs is scale. Scale insects look very different from typical garden insects. They are small, immobile and have no visible sign of antennae, and can resemble fish scales pressed tightly against the bark.

Felt scale on a tree trunk by United States National Collection of Scale Insects Photographs , USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.

There are many different types of scale including hard and soft-bodied scale. One scale that begins to show up this time of year is cottony fluff or felt scale. Felt scales look a lot like the Mealy Bug pest. They are white, soft, and look almost like a Q-tip. They are prevalent on urban willow oaks on the bark, branches, and twigs. The cottony sack that is visible now is the egg sack. If you were to dig around in the cottony material you would find small yellowish eggs. Once the eggs hatch they become what is known as “crawlers” and will move to an area of the tree and begin to feed on the sugary substance just beneath the bark. They also produce honeydew which is a sugary liquid by-product of many landscape pests that will attract ants and is sticky to the touch.

For more information on scales and other topics please contact the N.C. Cooperative Extension, Franklin County Center at 919-496-3344 or Colby Griffin at colby_griffin@ncsu.edu.